A new view of our 18th president

GREAT BARRINGTON He was among the best of presidents, he was among the worst of presidents — depending on which historians you believe, and there’s ample evidence to support both arguments.

Ulysses S. Grant, a West Point graduate, rose from clerking in his father’s leather-goods store in Galena, Ill., to become the great Civil War general who assured Union victory with the capture of Vicksburg, Miss., in 1863 and Richmond, Va., in 1865.

He accepted the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox. But as 18th President from 1869 to 1877, he supported Reconstruction in the South, but failed to confront the massive economic depression known as The Panic of 1873 (much as Herbert Hoover was unable to reverse the Great Depression of the 1930s). As a result, his administration fell apart, with its Justice, Interior, War and Navy Departments all riddled with massive corruption.

Historian Allan Nevins’s verdict: “Various administrations have closed in gloom and weakness … but no other has closed in such paralysis and discredit (in all domestic fields) as did Grant’s. The President was without policies or popular support … In its centennial year, a year of deepest economic depression, the nation drifted almost rudderless.”

Other historians and biographers have supported this harsh view.

But local historian Randy Weinstein , who created the Du Bois Center to honor Great Barrington native and civil rights pioneer W.E.B. Du Bois, begs to differ. A passionate advocate of a much more favorable overall assessment, Weinstein — a specialist in African-American history — cites Grant’s efforts to dismantle the Ku Klux Klan during the violent years of Reconstruction in the South, and his championing of civil rights for the newly freed slaves.

As Weinstein points out, it was Grant who advocated for and signed the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees that citizens may not be barred from voting because of race, color, or previous servitude (slavery).

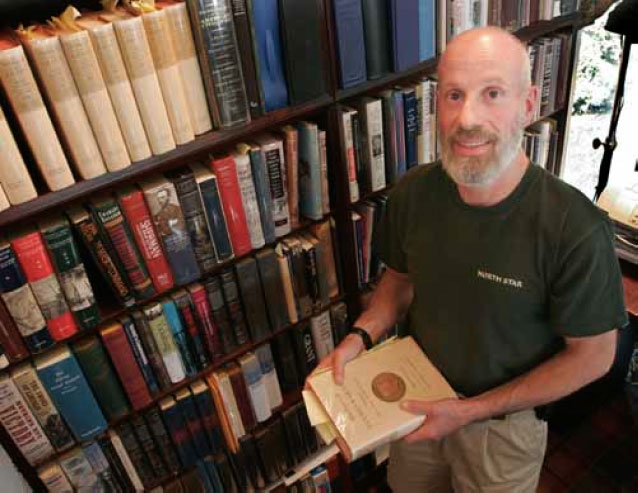

Weinstein’s mission is to help reverse Grant’s reputation as an alcoholic, a “battlefield butcher,” as well as an anti-intellectual leader who abandoned the blacks. The collector of rare books and manuscripts has assembled what he calls a one-of-a-kind exhibit of 100 volumes from Grant’s private collection, complete with annotations, signatures and other authentic touches.

Grant was a voracious reader (“addicted to Dickens and Trollope,” Weinstein notes) and an intellectual who counted among his admirers the likes of Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry James. The list of Grant’s friends includes Joseph Henry, director of the Smithsonian Institute, Andrew White, president of Cornell, statesman Hamilton Fish and Abraham Lincoln.

“People will never see a Presidential collection of this size in a private collection,” Weinstein asserts.

Weinstein, 53, is a former administrator of the defunct Kolburne School in New Marlborough, and he has written two books dealing with African-American history. The Norwalk, Conn., native, who moved to Great Barrington with his parents 40 years ago, opened the Du Bois Center in February 2006 at 684 South Main St., adjoining his North Star Rare Books & Manuscripts.

He traces his interest in the field to his work with “inner-city juvenile delinquents… bringing my passion for history into their lives.” Among Weinstein’s personal heroes is Du Bois admirer Frederick Douglass, the slave who became an abolitionist, author and statesman.

Both Douglass and Du Bois refuted critics of Ulysses Grant — according to Weinstein, “they felt Grant was going as quickly as the country could accept the reintegration of blacks into the South.” Weinstein’s once-revisionist view, now becoming more widely accepted, is that “Grant was our great civil-rights president.

“He has been thought of as someone who abandoned the blacks, but no one gave a damn about blacks in this country after 1872,” Weinstein declares. “The only one spitting in the wind was Grant. He sent the U.S. Army to destroy the Ku Klux Klan. He always felt his great accomplishment was the passage of the 15th Amendment. He went door to door, making house calls lobbying senators and congressmen for support.”

As for the books, Weinstein says Grant’s youngest son Jesse came into possession of the collection; in the year 2000, the Grant family decided to put it up for auction at Sotheby’s in New York City. But Weinstein and his business partner Glenn Horowitz, who’s based in the city, pre-empted the auction by purchasing the holdings prior to the auction.

Weinstein, who expects to complete a biography of Grant in time for publication early next year, says he decided to showcase the 100-book collection to benefit the local community. He reports that visitors have been “absolutely shocked” by the historical significance of the collection.

In spite of Grant biographer William S. McFeely’s criticism that, as president, Grant “abandoned the blacks,” Weinstein believes that Grant, formerly listed among the nation’s three or four worst leaders, is now beginning to pop up on the lists of top 10 or 15.

He asserts that Grant’s “Memoirs” — completed days before his death as he faced personal bankruptcy at a time when former presidents were not granted pensions — is one of the two great 19th-century works of non-fiction, along with the “Collected Speeches of Abraham Lincoln.” (Grant’s “Memoirs” sold a remarkable 350,000 copies when published, yielding the Grant family $450,000 in royalties, an astounding sum for 1885.)

After this summer, Weinstein’s collection of Grant’s books will be returned to New York City for a private sale. Meanwhile, Weinstein is convinced that the library “sheds new light on stereotypical, long-held views of Grant’s policies, beliefs, and achievements.

“I’ve been working with these books and I’ve got a national treasure here,” he says proudly. “The Smithsonian or the Library of Congress would have gladly put it on display.”

Highlights of Ulysses Grant’s library:

A personal copy of “The Federalist,” which Grant purchased at the age of 17 to prepare for entrance exams at West Point. It contains the earliest known Grant signature and his annotations, including comments on “the Constitution being the safeguard of Union.”

“War Powers Under the Constitution” by Lincoln’s chief legal adviser William Whiting, which provided the constitutional basis for the Emancipation Proclamation and for the military effort under Grant’s leadership. Grant’s annotations and comments are included in the copy of the book.

The memoirs of Confederate Army Col. John S. Mosby who met Grant in 1872 and abandoned his secessionist views, branding him a traitor by many Southerners. With Grant’s help, the unemployed Mosby became attorney for the Southern Pacific Railroad. The book, published in 1887, is inscribed to Grant’s widow, Julia.

Abner Doubleday’s classic memoir about Fort Sumter, published in 1876. Grant’s West Point schoolmate fired the first Union shot at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, following the start of the Confederate bombardment. On display is Doubleday’s inscribed copy for Grant, who annotated a lengthy section about the horrors of slavery.