Du Bois comes home from the grave

Local historian Bernie Drew, left, informs Arthur E. McFarlane II about the unmarked gravesite of his grandmother, Nina Yolande Du Bois Williams, in Mahaiwe Cemetery, in 2013.

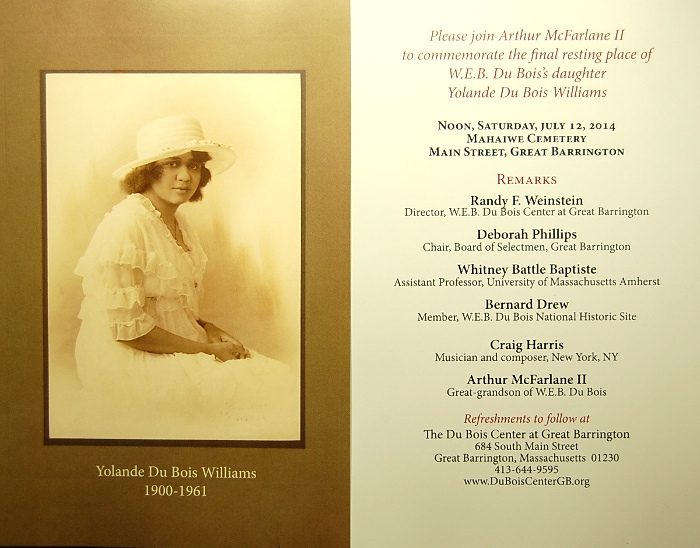

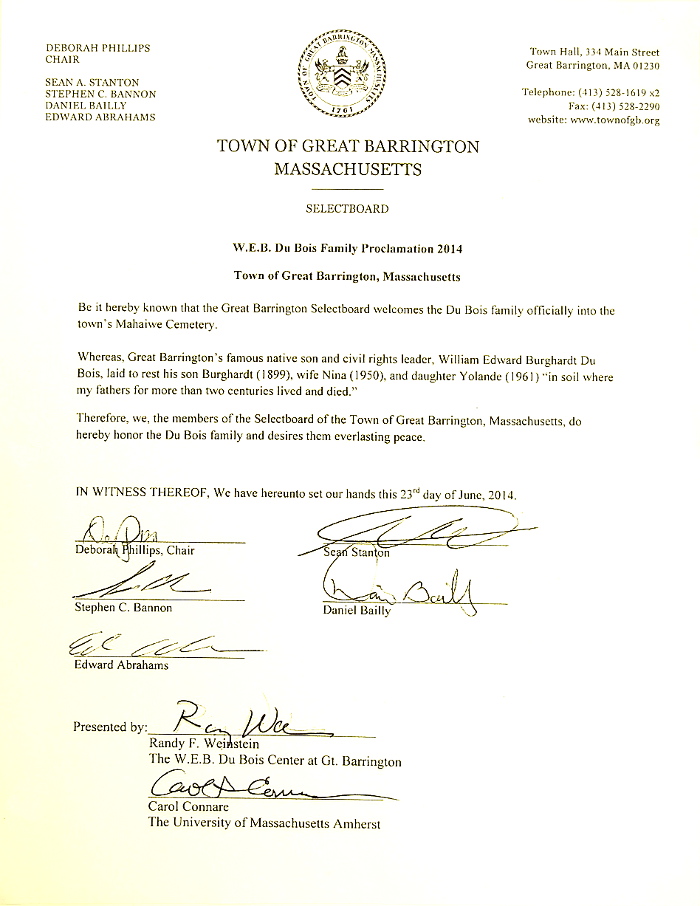

On Saturday, July 12, officials from the Town of Great Barrington, the University of Massachusetts and local residents are expected to pay their respects at Mahaiwe Cemetery as the great-grandson of W.E.B. Du Bois comes from Colorado to dedicate a headstone to his grandmother, Nina Yolande Du Bois Williams (1900-1961), more than 50 years after she was buried there without any fanfare.

The event is being organized by Randy Weinstein, executive director of the Du Bois Center of Great Barrington.

It’s almost as if Du Bois is coming home from the grave.

Back in March 1961, America was still in the grip of the Cold War. The battered scholar and activist W.E.B Du Bois was 93 years old. Although Du Bois had long been one of the world’s leading public intellectuals, and was destined to go down in the history books as the founder of America’s modern civil rights movement, the father of Pan-Africanism, and inventor of empirical sociology, among his innumerable distinctions, some of his countrymen treated him as a pariah on account of his radical political views. A decade earlier, for promoting international peace, his own government had tried him on trumped-up charges of being a “foreign agent,” (for which he was acquitted) and his passport was confiscated for eight years. He had suffered enormous abuse and disappointments and he was bitter.

W. E.B. and Nina Du Bois show off baby Yolande (b. 1900)

On that day in 1961 barely anyone noticed as Great Barrington’s most accomplished and controversial native son was making what would prove to be his final painful pilgrimage here before leaving the United States in self-imposed exile.

The old man’s face hung low with grief as he stood in his family’s snow-covered plot under the dark, wintry sky. He watched as the shiny coffin was lowered into the frozen earth, beside the graves of his first wife Nina Gomer Du Bois (1871-1950), and their infant son Burghardt (1899). Several others of his kin, including his beloved mother Mary Silvania Burghardt Du Bois (1831-1885), were interred nearby.

Presiding at the simple services was Rev. Frank Crook of the First Congregational Church, the church that Du Bois had often attended as a boy. His wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois, and a few others huddled with him in the cold and damp.

The recent sudden death of Yolande, his last living child, from a heart attack, struck him to his core.

“Why?” he had asked. “I am old; Yolande had so much life before her. Why should she go and I remain?”

For unknown reasons, Yolande’s grave was left without a headstone. Her grandchildren were unaware of where she was buried, until her grandson Arthur McFarlane II was informed of it during a visit in 2012.

Yolande as a young woman.

Yolande’s connections to the place form an important part of Du Bois family history. Like her old man, she had been born in Great Barrington – he in 1868, she on October 21, 1900, shortly after the parents had suffered the loss of their first-born from diphtheria in Atlanta, where Dr. Du Bois was teaching at the time.

In 1906 during a terrifying period of race riots in Atlanta, Du Bois had again sent Nina and Yolande back to his hometown for safekeeping and the girl had gone for a while to the same elementary school he had attended as a youth.

Yolande grew up to become one of the most prized mates of her Negro generation. For a time she carried on a torrid love affair with young Jimmie Lunceford, a bandleader in Harlem jazz clubs. But Yolande’s prickly father didn’t approve of jazzmen. Instead, her approved wedding in 1928 to Countee Cullen, a dashing literary leader of the Harlem Renaissance, was the Negro social event of the decade, bringing together two generations of America’s Talented Tenth. But the union ended in divorce in 1930 after it was rumored that Cullen was having a homosexual love affair with the “handsomest man in Harlem” – an intrigue that has since inspired a popular play, “Knock Me a Kiss,” by Charles Smith. It was a scandal of the black upper crust.

Yolande taught history at Baltimore’s Paul Laurence Dunbar High School and married a rough football player named Arnette Franklin Williams. In October 1932 the couple produced a daughter, Du Bois Williams (“Baby Du Bois”), but that marriage also soured and they too were eventually divorced in 1936. Du Bois Williams later grew up and married Arthur E. McFarlane and their children include Arthur E. McFarlane II, who is the Du Bois family descendant scheduled to visit Great Barrington in July.

When Yolande died, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote that “it seemed fitting that at the end of her life, she should go back to the hills of Berkshire, where the boy [Burghardt) had been borne [sic] and be buried beside him, in soil where my fathers for more than two centuries lived and died. I feel that here she will lie in peace.”

As for Du Bois himself, there seemed to be no place in America where he could find peace. His sharp-edged criticism of the United States government had further contributed to his growing isolation within the American civil rights movement. Although hailed as a visionary in other nations across the globe, he had become marginalized in his own country.

Shortly after Yolande’s passing, President Kwame Nkrumah invited him to Ghana to assume editorship of a monumental international research project, the Encyclopedia Africana. “I just can’t take any more of this country’s [America’s] treatment,” the old man wrote to a friend, Grace Goens, on Sept. 13, 1961. “We leave for Ghana October 5th and I set no date for return… Chin up, and fight on, but realize that American Negroes can’t win.”

Four days before his scheduled departure, Du Bois wrote a letter to the chairman of the Communist Party USA, saying, “Today, I reached a firm conclusion. Capitalism cannot reform itself; it is doomed to self-destruction.”

The newly independent Republic of Ghana was undergoing a scientific renaissance and the people welcomed him with reverence. “My great-grandfather was carried away in chains from the Gulf of Guinea,” the old man said. “I have returned so that my dust shall mingle with the dust of my forefathers.”

Du Bois carried on his work as long as he could. In 1962 he fell ill, but he fought it to the end. He died in Accra on Aug. 27, 1963, just hours before the historic Great March on Washington. He was 95 years old.

Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the NAACP that Du Bois had helped to found and later become estranged from, announced his death to the assembled masses. On the one hand, Wilkins praised Du Bois for his immortal 1903 book “The Souls of Black Folk,” remarking that it was Du Bois’s “voice that [called] to you to gather here today in this cause.” In the next breath, he quickly lamented that “in his later years Dr. Du Bois chose another path.”

From his grave in Africa, Du Bois had left his mark, and with poetic timing.

In death Du Bois has spawned wave upon wave of scholarship and tribute. He has been the subject of countless studies, including the two-volume magisterial biography by David Levering Lewis, which was awarded two Pulitzer Prizes.

Even the shorter accounts always mention that Du Bois was born and raised in Great Barrington. In the world’s eyes the town and the man are inextricably related. That is mostly because in his multiple autobiographical works, Du Bois always described in detail his upbringing and education, offering keen observations about the family, friends, mentors and influences that shaped him. Great Barrington was always in his mind. He felt safe here.

From 1928 to the early 1950s he owned his family’s former ancestral home on the edge of town and came back to visit it periodically. The boyhood site remains under archaeological study by UMass scholars headed by Prof. Whitney Battle-Baptiste. (UMass is also the institution that holds most of his papers.)

Articles by or about Du Bois have appeared in local newspapers since 1883. In recent years, there have been many efforts to preserve the legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois in Great Barrington. Local historian Bernard A. Drew has written extensively about his life. Local educator and bookseller Randy Weinstein has operated the Du Bois Center. Rachel Fletcher and other activists established the W.E.B. Du Bois River Garden along the Housatonic River Walk a few yards away from where Du Bois was born. His connection to the town is proclaimed on road signs, historical markers, exhibits, postage stamps, the $5 BerkShare paper money, flyers and graffiti.

Yet in 2006 a grassroots effort to name a new public elementary school in his honor failed to persuade the local school committee – even though he is doubtless the greatest alumnus of Great Barrington’s public schools and a textbook example of what public education can produce. In fact, the story of his local pursuit of education surpasses that of Abe Lincoln’s log-cabin hagiography, and much more can and should be done to advertise that inspiring example.

Barrington’s most famous native son is an icon who still attracts pilgrims from Africa, Europe, Asia and other distant lands. His stock may have gone up and down a bit over the decades, but the events planned for July may help to clarify how much his contributions are valued today in his formative hometown.