From Great Barrington to Ghana

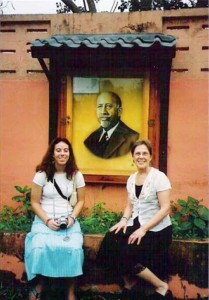

Becky Weinstein and Roselle Chartock in front of an image of W.E.B. Du Bois near the Ancestral

Graveyard, where two New York slaves were reinterred. Photos courtesy Roselle Chartock

A shot of one of the bleak and forbidding dungeon doors in Elmina. The monument outside the W.E.B. DuBois Memorial Center for Pan-African Culture in Accra.

Thursday, March 16 January 2006. Roselle Chartock and her small group had been in Ghana for two weeks and this was their last stop. They had traveled the slave trade route, seen canoes being built in the charming town of Elmina, watched the symbolic Kente cloth being woven, and descended 1,600 feet into the earth to watch gold miners. They toured forts that under the Portuguese had been trading posts, but which under the Dutch had become slave forts. She says she stood in the last door the slaves passed through before they boarded the boats for the middle passage, and a shiver went through her. Chartock is a professor of history at MCLA and also a Nazi Holocaust specialist. She travels to touch the history of a place, a people. But this trip was different. It was not her first trip, but it was a first trip—a kind of pilgrimage. And the last stop was the most important.

They were at the W.E.B. Du Bois Memorial Center for Pan African Culture, in Accra. Du Bois is buried there. “I made a tiny speech,” Chartock says. And then she gave them the things she had carried all the way from Great Barrington, the place of his birth, the place that throughout his life had still held some magnetized place in his heart — Du Bois buried his boy here in 1899, according to Randy Weinstein, director of the Du Bois Center of American History in Great Barrington, and then he came back 51 years later and buried his first wife here. Only the black revolutionary himself is not buried here.

“Du Bois was a pioneer of the civil rights movement,” says Chartock. One of his books, “The Souls of Black Folk” (1903), is “a book of essays that reveals the culture and dignity of black people.”

He was the founder of the NAACP, and for at least 25 years was the loquacious and vitriolic editor-in-chief of its primary mouthpiece, Crisis magazine. He also was instrumental in organizing several Pan African conferences, to bring attention to the problems of Africans around the world. In fact, Du Bois is considered the father of the Pan African movement—one that encourages all black people living in Africa to unite and believes that the diaspora, or those Africans spread out over the world, should identify with their African heritage.\

Du Bois spent the last two years of his long life in Ghana. He had gone there to work on an Encyclopedia of African American History, at the behest of Ghana’s first prime minister, Kwame Nkrumah. “There was a lot of turmoil that stimulated his desire to leave the U.S.,” says Chartock. In fact, he had been to Africa before, and had even written that the “spell of Africa is upon me.”

He was given a white stucco house in which to live, and when he died two years later, in 1963, he was given an elaborate state funeral. “I don’t know what happened between 1963 and 1985,” says Chartock, but 22 years after his death — in 1985 — the center there was established in his memory. “The intent was to provide a museum, library and educational center devoted to the Du Bois legacy,” says Chartock.

Chartock was uniquely qualified to plan and take this journey. She is not only a professor of history, but also a member of the board of the Du Bois Center of American History. Also, about 11 years ago, Chartock started what she calls study tours. “The best way you can learn about a culture is by going there,” she says. She started doing the travel tours because she wanted to see the world and she wanted her two children and her students to see it, too. For the first few years, she ran it mainly for students, but after that it became a community service.

She was taking part in a grant-funded program for the teaching of black history, and reflecting on her teaching of his life in her earlier career as a high school history teacher when she wondered if anyone had ever traveled from Du Bois’ birthplace in Great Barrington, to his grave in Ghana. It turned out no one had. And no one had ever brought anything from his birthplace to his grave.

She remembers thinking, “Maybe this is the place I was destined to go.”

And there was certainly stuff to bring. Year after year, Weinstein says, he saw people come from all over the world to visit graves in the Mahaiwe Cemetery. From his window at the bookstore, Weinstein could see the cemetery, where Du Bois’ first wife and only son, two uncles and an aunt are buried. “It was like sacred ground,” he says. He found himself giving unofficial tours, and then it occurred to him that he should commemorate the importance of Great Barrington to Du Bois” life.

So it was while Chartock was making her final travel arrangements that Weinstein was knocking down walls and dumping his life savings into what is now a 3,000-square-foot center. “We have a performing arts/lecture area with 80 chairs, a conference area, a number of artifacts, including Paul Robeson’s contract to play “Othello” on Broadway, and more than 2,000 books on African-American history and culture,” says Weinstein. The center is also the Great Barrington Historical Society’s permanent visitor center.

Du Bois always had a connection with Great Barrington, Weinstein says. “People have had letters from him as recently as 1961, warning about the danger of polluting the Housatonic or encouraging them to work to keep the quaintness of Main Street.”

“He was just a local boy makes good,” says Weinstein, simply. “His heart was always in the Berkshires.”

Outside of the center, other groups were doing their part to sustain Du Bois’ local legacy. Rachel Fletcher and Bernard Drew, members of Friends of Du Bois, were working to preserve his home site.

After she got the idea to go to Ghana, Chartock started digging. UMass has a lot of Du Bois’ papers—so she contacted them and learned that Bill Strickland, a professor of African studies there, had gone to the center in Accra in 1986, the year after it opened. He delivered some of Du Bois’ papers on microfilm. Strickland gave Chartock the name and e-mail address of the center’s director — Anne Adams, a professor of African studies at Cornell. Adams had done a sabbatical at the center, which then tapped her as its full time director when she retires. Adams gave Chartock the name of the acting director and the special projects director at the center in Ghana.

“We didn’t just want to show up,” Chartock says. “My mission was to bring a group from his home site to the place of his burial and at the same time deliver documents that reflected what we are doing to preserve his legacy.” When she talked to Adams, Chartock also invited her to the February 11 opening of the center in Great Barrington. The opening was so big that it couldn’t be held in the center—instead, it took place at St. James Episcopal Church. Adams was there.

Weinstein says he would have liked to go on the journey to Ghana, but he was too busy with the opening of the Center. His daughter Becky went instead. Richard Courage, who lives in Great Barrington and who, like Chartock, is on the board of the Center, went as well. Seven students and one teacher — James King from Simon’s Rock — also went on the trip. King is also on the board.

“He turned the trip into a course,” says Chartock, of King. “We went to learn Ghanian culture, crafts, history, and mostly, the fact that Ghana, also known as the Ivory Coast and the Gold Coast, was a place of extensive slave trading.”

The group stayed in Accra for one day, and then departed for the slave forts in Cape Coast and Elmina. They stopped in the small town of Assin Manso along the slave trade route, where slaves where bathed and checked for fitness before being taken to the coast for shipment out of Africa. Chartock and Weinstein’s daughter, Becky, posed for a photo before a large image of Du Bois. “There were 15 large photos there,” Chartock says. “There were a lot of African Americans — Frederick Douglas, Martin Luther King.” There was the ancestral graveyard nearby, a memorial where the bodies of two slaves — Samuel Carson from the U.S. and a woman known as Crystal from Jamaica — are buried. Their remains were flown to Ghana in 1998 and reburied.

They went to the city of Kumasi, the seat of the Ashanti empire, a tribal group known for their fierce fighting. They came back to Accra for the last two days of the trip, and on that Friday morning, they kept their most important appointment.

The things Chartock brought, the things she gave them, reflected the homage paid by a local community to its native son. Among them were a booklet that Rachel Fletcher and Frances Jones Snead had put together, called “Historical References to Berkshire County and African American History”; a copy of a play that Nickey Friedman wrote about Du Bois, which was performed two years ago at Berkshire Country Day School; some artwork and poetry written by some of the students at that school; a booklet of photos of several contemporary sites related to Du Bois; Bernard Drew’s guide “50 Sites in Great Barrington, Massachusetts Associated with the Civil Rights Activist W.E.B. DuBois;” and a beautiful bound volume of excerpts of famous writings by Randy Weinstein , director of the center in Great Barrington.

There were other things too, all of them local, all of them a small offering up to the memorial of a man who lived to the ripe old age of 95 and who was an intellectual, a social and political pioneer, and a prolific writer for pretty much all of those years.

“There are tons of things going on about Du Bois,” says Weinstein. “UMass has the world’s largest archive of his writing. Here at the center we’ve got a number of original manuscripts, and books inscribed from him to friends.”

There are Du Bois centers at UMass and at Harvard, but the center in Great Barrington is open 7 days a week, it’s free, and the public is welcome. “We’ve got a bookstore and a reference center for students,” Weinstein says.

“How does a town commemorate and honor its favorite son — name schools, road signs, affiliate yourself with other centers; and you make a center like this, where people can come in and get answers,” says Weinstein. A historian himself, he quibbles with the later recorded matters of Du Bois’ life — the matter of his citizenship and his reputed communist leanings. “If you read his letter to the American communist party,” Weinstein says, “You would know that he was really looking for a viable third party option to the existing American political system.”

Over in Ghana last month, Roselle Chartock connected these not so different towns at either end of Du Bois’ life. She offered her gifts and made her tiny speech. “I told them how wonderful it is that we can make a connection between Great Barrington and Accra. I told them I hoped they would be able to visit his birthplace — our town — as we have visited his grave.” She even offered up her own house for lodging.

No matter where he’s buried, it seems Du Bois will always have a special place in the hearts of these people and this town.

Chartock is giving a slide presentation about the journey at Club Helsinki in Great Barrington on March 26 at 12:30 p.m., called “W.E.B. Du Bois — From Birthplace to Burial Site.”