Indigenous Peoples Day

‘One human family’

Love and prayers at Great Barrington ceremony and an offering to the river

BY HEATHER BELLOW

The Berkshire Eagle

GREAT BARRINGTON They stood on the bank of the Housatonic River and prayed to the four directions in the presence of a Navajo warrior staff and guarded by the spirit of the eagle.

Lev Natan, whose nonprofit organized the town’s first Indigenous Peoples Day ceremonies for Monday, scattered an offering of tobacco and Pacific seashells imbued with prayers into the river. His grandfather, Jake Singer, a Navajo medicine man and Sundance Chief, stood by after leading the prayers, and next to him was Shawn Stevens, of the

Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians the people pushed from these lands who eventually settled in Wisconsin.

The river flowed and sparkled with autumn light, and above the banks stood at least 100 people who had walked through the downtown to drumbeats and song to honor the people who once lived here and across what is now called the United States. Most were scattered from their homelands or killed by war and imported disease, as colonists and the government tried to eradicate their cultures.

“It was designed to make us implode from the inside out,” said Stevens, speaking earlier at the town gazebo, noting the mission schools for Native American children meant to strip them of their heritage. “People did not want us to be spiritual and cultural.”

By the time Native Americans could practice their own religion again in 1978 it was too late to staunch a wound that would weave through generations to come, and the many trails of tears. But then came the birth of the White Buffalo Calf in 1994, in the same Wisconsin town where Stevens was born, an omen of coming change to Native Americans.

“Things began to change slowly, very slowly,” Stevens said.

Perhaps this holiday is part of those slow changes. Great Barrington is one among a growing number of communities, and school districts, in Berkshire County that have officially embraced pushing Columbus Day back into the annals of conquest and tyranny past and shifting to Indigenous Peoples Day.

On Friday, President Joe Biden made the first-ever federal proclamation of Oct. 11 as Indigenous Peoples Day, with a promise to honor the trust and treaty obligations of the federal government to tribal nations.

Natan, founding director of Alliance for a Viable Future, had been inspired by Randy Weinstein and Gwendolyn VanSant to create the ceremonies, one day of several events. The two are co-chairs of the town’s W.E.B. Du Bois Legacy Committee, and had asked town officials to consider renaming the holiday.

Absent Monday was a politicized atmosphere of division and strife. Natan, Singer and Stevens called for love of each other and protection of the earth.

“We actually are all relatives, we’re one human family,” Natan said.

Singer, who is also a Vietnam veteran, wore a Navajo war bonnet and said the prayers for the earth and people are for everyone.

“Regardless of color, race or religion and creed,” he said. “We’re all the same, we all come from the same great spirit, so in a way we are all brothers and sisters, and we shouldn’t fight amongst each other, love one another and take care of one another.”

Aaron Athey, a Mohican medicine man, a chaplain for the Connecticut Department of Corrections, and a music and song leader, said it is important to share the culture.

“To bring love back into the community, to repair this earth, and to love and to do healing,” Athey said.

Certainly, much is needed. Dennis Powell, president of the Berkshire County chapter of the NAACP said that African Americans can relate.

“We, the NAACP, know fully well why we stand in solidarity with our indigenous people, because we also know what it’s like to have your identity stolen,” he said, noting his dismay that all of the Berkshires hasn’t united in proclaiming this day of honor.

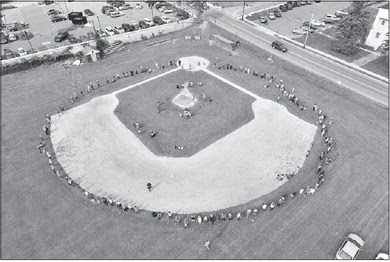

But, in Great Barrington, people prayed. One by one they made their prayers at the gazebo, and those were then carried to the Housatonic River Walk in a procession of drumming and song. Later, they would gather in a circle at Memorial field.

Earlier, Stevens explained what the word Mohican means, and that the people historically lived on lands from the bottom of Lake Champlain in Vermont down to Manhattan, on both sides of the Hudson River.

“‘Mahi’ which means ‘great,’ and ‘hican’ which means ‘a body of water that flows in different directions,'” he said. “It’s not a river, it’s not a lake, it’s not a pond, it’s a body of movement that goes in many directions.”

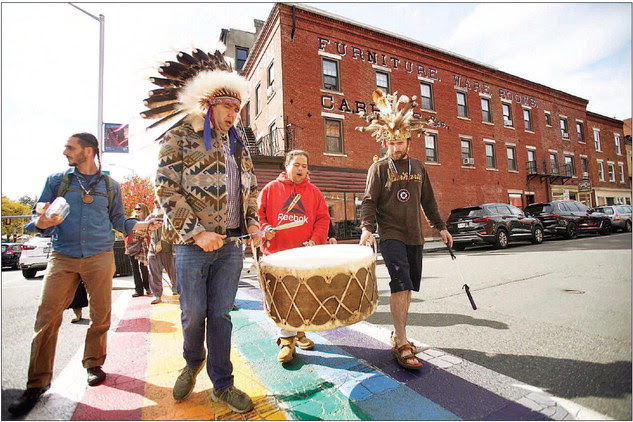

Lev Natan, left, and Aaron Athey, second left, lead marchers toward the Housatonic River during an Indigenous Peoples Day celebration in Great Barrington. Athey, a Mohican medicine man, a chaplain for the Connecticut Department of Corrections and a music and song leader, said it is important to share the culture, “to bring love back into the community, to repair this earth, and to love and to do healing.” Natan’s nonprofit, Alliance for a Viable Future, organized the ceremonies. PHOTOS BY BEN GARVER THE BERKSHIRE EAGLE

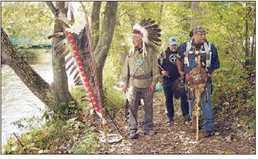

Jake Singer, left, a Navajo medicine man and Sundance Chief, and Shawn Stevens. right, of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians, prepare to make offerings to the river during the celebration.

Participants made prayer offerings of tobacco and white seashells at the celebration. PHOTOS BY BEN GARVER THE BERKSHIRE EAGLE

Attendees made a great circle for prayer around a baseball diamond in Great Barrington during a celebration of Indigenous Peoples Day on Monday.