The post-Civil War roots of Du Bois’ work

Center explores context of a civil rights pioneer’s legacy

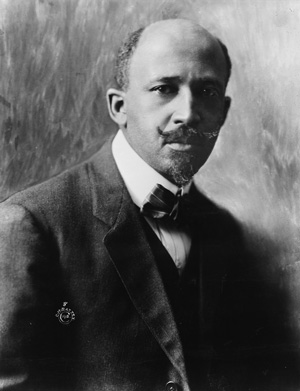

W.E.B. Du Bois wasn’t born until three years after the Civil War ended, but the war and its aftermath were crucial in shaping the views of one of the nation’s first prominent African-American scholars and civil rights activists.

With 2015 marking the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, the historical context of that era has become a new focus of inquiry for Randy F. Weinstein, the executive director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Center at Great Barrington, here in the town where Du Bois was born.

Du Bois, for example, was a great admirer of Ulysses S. Grant, the Union general and later two-term president who pushed to wipe out the last vestiges of slavery and to establish the citizenship rights of blacks in the former Confederacy.

So lately Weinstein has been considering how to set up an exhibit that would focus partly on Grant and, at the same time, examine how Grant’s achievements inspired and influenced Du Bois.

Adding depth and historical context to the public’s understanding of Du Bois’ work is part of the mission of the Du Bois Center, which Weinstein founded in 2006 after a series of controversies over how Great Barrington should honor its native son.

Weinstein is the author of the award-winning book “Against the Tide: The African-American Experience, 1711-1987,” published in 1996. After 30 years of working with emotionally challenged children in the southern Berkshires, he said he felt compelled to find a meaningful way to honor and celebrate Du Bois’ life and work.

With his background as a teacher, caseworker and administrator at the now-defunct Kolburne School in nearby New Marlborough, Weinstein wanted to create an institution whose mission would remain solidly educational – another nod to Du Bois’ legacy.

“Du Bois was not only a significant figure in American civil rights history, but also in our intellectual history too,” Weinstein said. “Today, there is so much focus on his writing and activism that people forget what a pioneer he was as an American scholar. He was the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. in this country.”

Du Bois’ scholarship gave intellectual heft to his civic engagement later in his life, Weinstein said. As a professor of history, sociology and economics at Atlanta University, he was a prolific author and advocate, and he became one of the founders of the NAACP in 1909.

“The seeds were planted right here in Great Barrington, a place that you can say he has been both loved and loathed,” he said.

The loathing mainly stemmed from Du Bois’ on-and-off associations with the Communist Party, a connection that led to his indictment, at the height of the McCarthy era, on charges of being an unregistered agent of the Soviet Union. The case was ultimately thrown out of court in 1951.

Du Bois later did join the Communist Party, however, and spent the last years of his life in Ghana, where he became a citizen before his death in 1963 at the age of 95. That history has led some to conclude that Du Bois rejected his native country – a conclusion his defenders dispute.

Discovering Du Bois’ roots

Discovering Du Bois’ roots

Du Bois was born in 1868, in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, amid Reconstruction and the emancipation of slaves. During his boyhood, his hometown of Great Barrington was relatively tolerant in its social attitudes, and it was integrated.

Weinstein said he knew of Du Bois from his earliest days — from a most appropriate source.

“I grew up in Connecticut during the ‘60s, and my nanny, Rebecca Alexander, was the granddaughter of South Carolina slaves,” Weinstein said. “This influenced my world view for life. I went everywhere with Becky — out shopping, to church. I heard the first mention of names such as Martin Luther King Jr. and W.E.B. Du Bois when I was with her. I wanted to know, from childhood, who they were and why they kept coming up.”

After Weinstein moved to western Massachusetts for college and then went to work at Kolburne, he learned more about Du Bois’ local legacy.

Du Bois attended public schools and did what he could to help support his single mother Mary, who died in 1885 when he was 17. He worshipped at the First Congregational Church, whose congregation helped to pay for his undergraduate studies at Fisk University in Tennessee, where he earned his first bachelor’s degree.

“Armed with the work ethic he developed here in the Berkshires as a boy, Du Bois then paid his way through another two degrees from Harvard, and went abroad and studied in Germany,” Weinstein said.

Du Bois’ mentors included William James, who was arguably America’s most influential philosopher, and the economist Adolph Wagner, who helped shape many of Du Bois’ ideas of how the state can enhance the citizen’s life – a notion that made his work controversial as he became more prominent later in life.

Local debates: schools, signs

Weinstein’s decision to create the Du Bois Center had its beginnings in a pair of local controversies a decade ago in Great Barrington.

First, in 2004, some citizens urged the Berkshire Hills Regional School District to name its new elementary school building in honor of Du Bois. But the local school committee wound up rejecting the idea after a long and bitter debate.

“The naming of the new school was really baffling for a lot of us,” recalled Nichole Dupont, a freelance writer, activist and former teacher from Sheffield, the next town to the south. “The options that were on the table seemed so bland and completely irrelevant compared to naming the school after Du Bois. But people were very passionate about not giving the school that name.”

Instead, the school committee chose an innocuous name based on local geography: Muddy Brook Elementary School.

The next year, the town selectmen were asked to put up road signs at the entrances to Great Barrington to identify the town as the birthplace of Du Bois. The board initially rejected the idea – only reversing itself after voters at town meeting approved a nonbinding resolution supporting the signs.

It was then that Weinstein, who in addition to his work at Kolburne also had become the proprietor of North Star Rare Books on South Main Street, decided his collection of relevant period Americana was a good start for an educational center focused on the life of Du Bois.

“The idea for the Du Bois Center grew out of and around many of the artifacts and documents at North Star which were centered in the African-American experience,” Weinstein explained. “Our purpose is to examine history honestly and study all aspects of social justice.”

His bookstore remains affiliated with the center, which is within view of the Mahaiwe Cemetery, where Du Bois buried his wife, Nina, daughter Nina Yolande and 2-year-old son Burghardt.

It is there that a crowd gathered in July for the formal dedication of a new stone on the grave of Nina Yolande Du Bois Williams – a ceremony organized by Weinstein and attended by Nina Yolande’s grandsons, Arthur McFarlane and Jeffrey Peck.

Looking ahead: An exhibit on Grant?

Today, the Du Bois Center includes a research library and a subsidiary, the Museum of Civil Rights Pioneers, established in 2011.

Weinstein envisions continuing its educational mission, focusing on programs involving schools, and offering regular displays and the occasional interpretive exhibitions that sample the broad spectrum of the civil rights movement beyond the work of Du Bois.

One of those could involve a focus on Ulysses S. Grant.

“He was the general who freed the slaves,” Weinstein said. “Others tried, but Lincoln didn’t find his man to defeat the Confederacy and Robert E. Lee until landing Grant. So lending some insight into Grant the man, particularly in light of his fervent support of the 15th Amendment in his first months as president, would be a very dynamic exhibit to bring to the center.”

Weinstein said one possible way to do this involves two artifacts owned by the center. The first is a signed dedication volume of Du Bois’ “Black Reconstruction,” which Weinstein called “one of the center’s jewels.”

The other is an annotated 1826 edition of “The Federalist,” which Grant bought as a teenager, just before entering West Point, to better prepare himself for the rigors of his future studies. Along with his written notes, the book also contains Grant’s earliest signature on record.

“Grant won the Civil War, which ended slavery,” Weinstein said. “To have notes in Grant’s own hand in the book which was the conceptual foundation of our nation, next to a signed book on the Civil War’s social aftermath by Du Bois, who had praised Grant as a liberator — well, there are quite a few important American stories to tell there.”

Ethan Rafuse, a military historian and professor of history at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in Fort Leavenworth, Kan., said Grant opened doors to the future for someone like Du Bois.

“Grant was one of the most important figures in the revolution the Civil War wrought in American race relations,” Rafuse said. “As the first Union forces to undertake major offensive operations in the western theater, Grant’s army served as an agent of liberation well before emancipation became official policy of the U.S. government.

“Grant’s views evolved to the point where he viewed attacking slavery as essential to achieving victory,” he added.

And that forceful stance must have been an inspiration to Du Bois, who in the realm of the nascent civil rights movement opposed the prevailing approach of accommodation articulated by Booker T. Washington.

Instead, in his groundbreaking 1903 book “The Souls of Black Folk,” Du Bois called for “ceaseless agitation and insistent demand” and the “use of force of every sort: moral suasion, propaganda and where possible even physical resistance” to achieve equal rights for African-Americans.