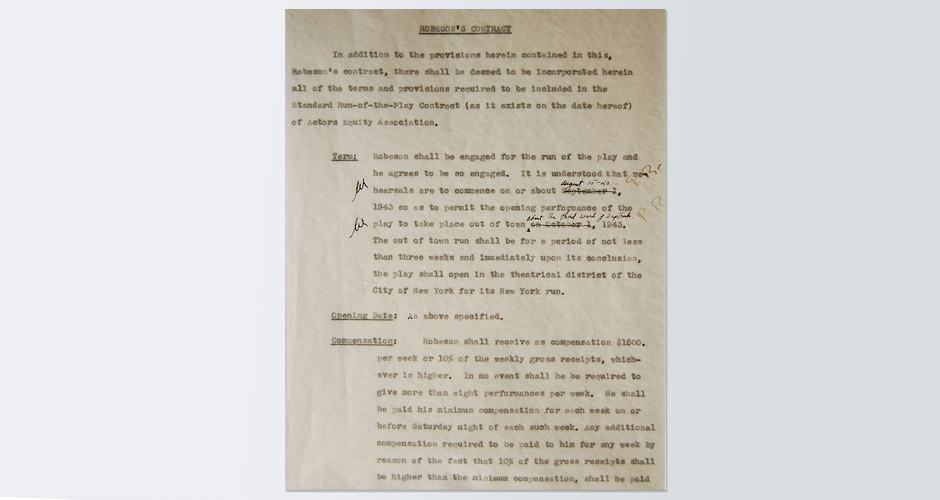

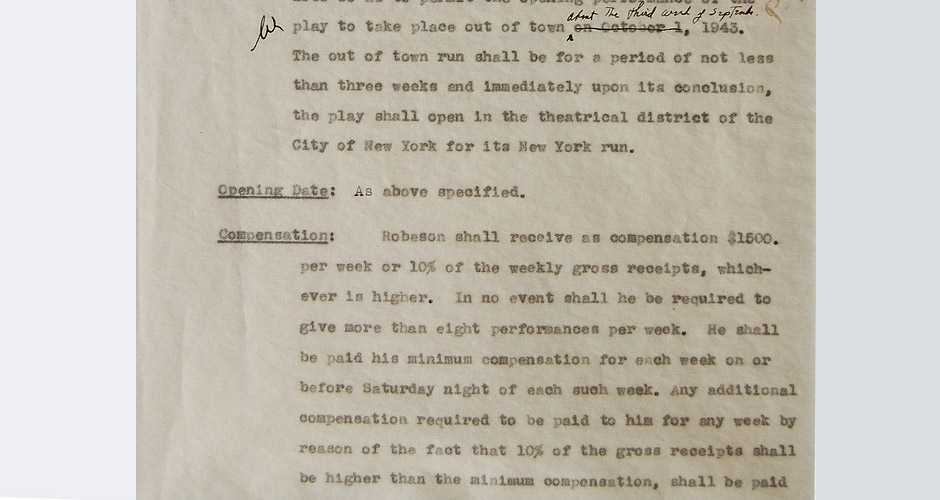

Paul Robeson, Othello (The Theatre Guild, 1943). Typed document, entitled “Robeson’s Contract”: three-page contractual understanding to produce Shakespeare’s Othello; signed and annotated by both Robeson and Lawrence Langner, January 26, 1943.

During the summer of 1930, fifteen years after his first high school attempt at playing Othello, Robeson burst upon the English stage. While the historic but reserved performances brought international recognition, Robeson’s dream of starring in an American production was thwarted for more than a decade, stage director Margaret Webster conjectured in Our Time, “because an American audience would never come to see a black man play a love-scene with a white woman.” Nevertheless, the Phi Beta Kappa scholar persisted to study – telling a Daily Express reporter that the Shakespearean tragedy released “all sense of limitation, and all racial prejudice. In a word, Othello has made me free.”

In the early 1940s, Robeson and Webster decided to test the waters together. A veteran cast was assembled (with the crucial roles of Desdemona and Iago assigned to Uta Hagen and Jose Ferrer; Webster herself played Emilia), and tryouts were scheduled in Cambridge and Princeton (Robeson’s birthplace). During August 1942, the racially mixed company gave laudatory performances at the Brattle and McCarter Theatres. Producers expressed interest. The Theatre Guild’s provident founder, Lawrence Langer, Robeson’s friend since the early 1920s, agreed to assume financial control of the show. Contracts were drawn up for Robeson, Webster (director), and Haggott (manager-technical advisor). Playwright Eugene O’Neill’s versatile colleague, Robert Edmund Jones, was recruited to design sets and costumes.

Robeson’s contract, finalized on January 26, 1943, stipulated a weekly salary of $1500 (or ten percent of the weekly gross receipts, whichever was higher), with an added clause assuring no more than eight performances each week. According to the contractual arrangement, “all matters pertaining to artistic aspects of the production shall be under the… control and supervision of Robeson, Webster, and Hagott, provided, however, that final selection of the cast and Robeson’s costumes shall be… with Robeson.” (On one occasion, when the Guild insisted on replacing Ferrer and Hagen, Robeson brandished this contract and threatened to quit the production unless the husband-and-wife team stayed on. The Guild conceded.)

“For the first time in the United States a Negro was playing one of the greatest parts ever written and the occasion was trying to prove something other than itself,” Webster recalled, when the play premiered at the Shubert Theatre on October 19, 1943. NAACP executive Walter White later told Langner that “the playing of a Moor by a Negro actor” (Robeson’s portrayal was “one of the most inspiring and perfectly balanced performances I have ever seen”), had raised the “hope that race prejudice is not as insurmountable an obstacle as it sometimes appears to be.”

Before Othello ended its Broadway run in the summer of 1944, the 46-year-old tragedian had harvested a plethora of awards, including that of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The record-breaking 296 performances were the supreme moment of Robeson’s artistic career and, in Webster’s words, a “landmark of American social consciousness.” Decades after Othello riveted Broadway, poet Robert Hayden paid homage to Robeson: “Call him deluded, say that he was dupe and by half-truths betrayed. I speak him fair in death, remembering the power of his compassionate art. All else fades.” A cornerstone piece of African Americana.