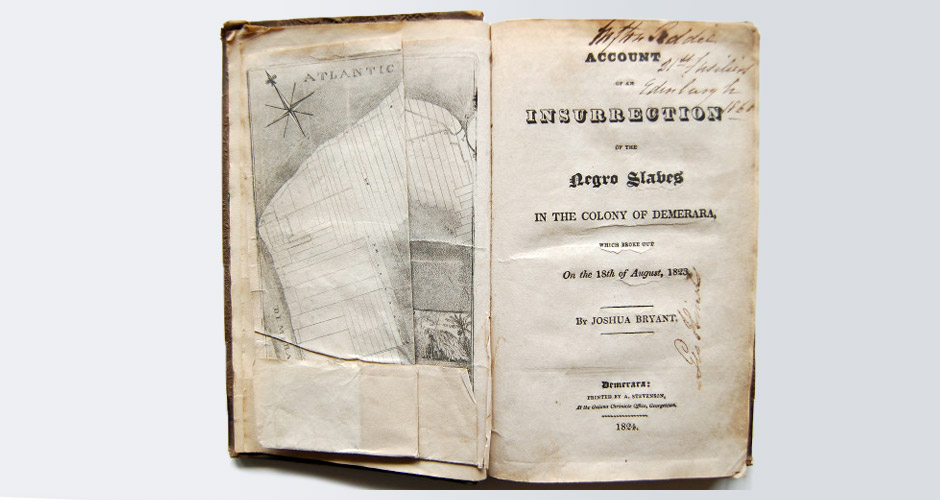

Joshua Bryant, Account of an Insurrection of the Negro Slaves in the Colony of Demerara, Which Broke Out on the 18th of August, 1823 (Georgetown: Guiana Chronicle Office, 1824). 8vo., Inserted folding map and 12 copper engravings, 3/4 calf, floral patterned cloth, black morocco label stamped in gilt; several nicked plates; Barbados bookseller ticket. First edition of the “first history of the Demerara rebellion.” Sabin 8809. An exceedingly scarce book.

The NUC lists four copies, The British Museum Library another. Two of the known copies lack complete maps and plates as described (pages 115-120) by fifteen-year Demerara resident and artist Joshua Bryant.

Captain J. Crofton Peddie’s copy, with “C. Peddie, 21 Fusileers” engraved on the lower spine label. Peddie, a member of the court charged with the arraignement of insurrectionist John Smith, is listed on page 91. Peddie’s ownership signature appears several times; the final blanks are covered in his hand, with approximately 500 words detailing his arrival in Demerara (1821) and subsequent involvement with the proceedings.

On October 13, 1823, John Smith, a thirty-one-year-old Methodist missionary with unassailable anti-slavery convictions (assigned to administer “religion” to three hundred ninety-six slaves on Le Resouvenir plantation), was formally charged with inciting one of the largest slave rebellions in New World history. The uprising of some ten thousand Demerara slaves was precipitated, in great part, by rumored dispatches of pending parliamentary measures aimed at ameliorating slave conditions (the promotion of religious instruction and assurances of family immunity from the slave trade) as a prerequisite step toward eventual manumission. By August 1823, slaves on some fifty plantation, surmising through the frenzied reactions of planters that “their rights” were being withheld, overtook the colony. Innumerable cutlasses, knives, sticks, and guns were brandished with self-control (two or three belligerent whites were executed), and emancipation was demanded.

The Gandhi-like protest produced a massacre. J. Crofton Peddie, one of the fifteen officers to weigh the case against Smith, was ordered to secure Le Resouvenir (the site of Smith’s chapel, said Joshua Bryant, where the “revolt had been fixed”), and days later, at Bachelor’s Adventure plantation, the captain participated in the largest, bloodiest battle of the three-day insurrection (where colonial forces, numbering around four hundred fifty men, opened fire upon some three thousand slaves, killing about two hundred). Ordered to join the militia, Smith refused and was arrested on grounds of promoting “discontent and dissatisfaction in the minds of the Negro Slaves” and for conspiring with his chief deacon and principal insurgent “against the King, his Crown and Dignity.” The proceedings lasted twenty-seven days. On November 24th, he was sentenced to death, pending a reprieve from the King-in-Council. Smith languished in a Georgetown jail. Word of clemency arrived on March 30th, almost eight weeks after the London Missionary Society zealot had expired from “pulmonary consumption.”

Parliament became a powder-keg, nearly ignited by public outrage over Smith’s “martyrdom.” Never before was the appeal to end slavery more decisively pressed. The intended reforms that had shaken Demerara into rebellion were instituted with speed. Emancipation by apprenticeship was achieved, as the government begrudgingly promised, a decade later, after which Frederick Douglass told Englishmen: “[T]he [Demerara] slaveholder hated, persecuted, burned the chapels, and rendered insecure the life of the missionary, [but] Religion there assailed slavery: it cried aloud and spared not, but lifted up its voice like a trumpet against it.”